Sense Active report 2022

Understanding the physical activity needs of families who have children with complex disabilities.

This report outlines the key findings from the research and sets out recommendations for all sports providers to consider when delivering inclusive activities. Sense have used these to develop an action plan of steps they will take.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all of the parents and carers of children with disabilities who contributed to this research, without whom this report would not be possible.

For both the survey and focus groups we have required input, knowledge, and time from a range of individuals, through a challenging period. We hope the findings and recommendations lead to improved physical activity opportunities to you and your family.

Executive summary

Sense launched ‘Sense, Active Together’ with funding from Sport England, to ensure all children and young people have the opportunity to get the best possible start in life, by building on their existing sport and physical activity offer for children and young people with complex disabilities, as well as their families.

Sense commissioned the ukactive Research Institute to undertake a research consultation to understand the physical activity needs of families who have children with complex disabilities. This involved an:

- Online survey (January – March 2020) exploring challenges, barriers, motivators and activity preferences of parents and carers of children with complex disabilities. 127 parents and carers responded.

- Three focus groups and 13 interviews with 24 parents and carers exploring these survey themes in more detail.

Motivations and barriers experienced by parents and carers

Motivations

For their child’s physical health, enjoyment and stimulation, mental wellbeing, and social interaction and inclusion.

Barriers

Limited activity options (too far away, wrong timings), locations not offering one-to-one support, restrictive access to locations.

Inclusivity by design (person-centred approach) and accessibility

Recommendation

Cater physical activity opportunities by need, and categorise by intensity or ability instead of age so activities can be easily identified.

Recommendation

Develop and design physical activity sessions utilising a co-creation, person-centred approach, ensuring access and engagement in suitable activities for a range of complex disabilities. Ensure sessions are flexible in structure, timing, delivery (online and in person) and collect continuous feedback to modify and update activities.

Communication

Recommendation

Ensure communication of physical activity opportunities is clear and detailed to allow parents, carers and children to prepare. Information should be included on content, ability level, adaptation and accessibility.

Recommendation

Provide and improve support networks for parents and carers who use your services to allow opportunities for individuals to socially connect and receive information, guidance and advice from others experiencing similar situations or needs.

Instruction

Recommendation

Ensure physical activity sessions are being led by appropriate individuals who have the confidence, competence (skill) and interpersonal abilities to adapt sessions to cater towards need and build positive relationships with the children.

This research has indicated the importance of ensuring that physical activity offerings are inclusive for all children, no matter how complex their disability, to ensure they have equal opportunity to fulfil their potential and obtain physical and mental health benefits.

Introduction

It is important that all children and young people are provided with the opportunity to get the best possible start in life. However, for some, and their families, this is not possible for various reasons.

Additionally, there are an estimated 73,000 school-aged children in England with complex needs and life-limiting conditions(3,4). Children and young people with multiple disabilities present with unique needs and challenges (5).

This can include impairments with cognition, motor, and sensory functions which can occur in combination with each other(5).

Children and young people with multiple disabilities often find it challenging to engage with the world they live in, from communicating their wants and needs to freely moving their body and understanding abstract concepts and ideas(5). Providing support for these children and young people, and their families is vital.

For children and young people without a disability it has been suggested that without the involvement of family members, it is unlikely that long term physical activity promotion is possible(6).

Furthermore, interventions that are family-based and promote physical activity for children have been effective, with 66% demonstrating a positive effect on physical activity(6). Previous research suggests that parents value the role of physical activity for children with complex disabilities, but they lack the skills required to confidently engage their children(7).

This presents an opportunity for physical activity-based interventions to engage children in activities and support parents to develop the required skills to enhance recreational activity opportunities for their children (7).

Barriers and motivators that impact participation in physical activity for children with a disability include personal, social, environmental aspects as well as those related to the policy and programme delivery (8).

More specifically, barriers to participation in physical activity engagement include a lack of knowledge or skills, preferences from the child and the parent’s behaviour, fear, negative attitudes towards disability, a lack of transport as well as inadequate facilities, programmes and staff capacity and cost(8).

Key motivators for engaging children with disabilities in physical activities include providing them with the choice of activities and providing these through inclusive pathways that encourage continuous participation as skills develop and children grow(9). This includes a child’s desire to be active, to practise skills and the involvement of friends as well as family support(8).

Having accessible facilities, the location proximity, appropriate opportunities, having skilled staff and available information are also key motivations(8). The promotion of activities, improvement in access to opportunities and highlighting the importance of engagement in physical activity for children with disabilities could be improved and facilitated through partnerships between providers of physical activity, schools, disability groups, local councils and the health sector(9).

To ensure that all children and young people have the opportunity to get the best possible start in life, Sense launched ‘Sense, Active Together’ with funding from Sport England. ‘Sense, Active Together’ aims to build on the existing sport and physical activity offer for children and young people with complex disabilities, as well as their families. This is a three-year programme that will engage and support over 2,500 people with complex disabilities to become active. (August 2019 – July 2022, now extended until March 2023 due to the coronavirus pandemic delaying delivery.)

Evidence that physical activity has a positive impact on health is well established, including an association with better physiological, psychological and psychosocial health among children and young people(10)(11). This includes improved cardiorespiratory and muscle fitness, cardiometabolic health (blood pressure, dyslipidemia, glucose, and insulin resistance), bone health, cognitive function, mental health (reduced symptoms of depression) and reduced adiposity(12)(13). Many of these health benefits of regular physical activity relate to children and young people living with disabilities(13).

However, the additional benefits of regular physical activity for children and young people with disabilities include improved cognition in those with diseases or disorders that impair cognitive function (including attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, or ADHD, and improvements in physical function which may occur in children with intellectual disability(13).

In fact, for the first time, the recently updated ‘WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour’ recommend the same amount of physical activity for children and young people irrespective of whether they live with a disability or not, with some physical activity being better than doing none(13).

However, Sport England’s Active Lives data suggests that for children aged 5-16 years less than half are classified as active, with just under a third classified as inactive(14). Although these findings are similar for children both with and without a disability or long-term limiting health conditions (14), participation in physical activity for children with a disability and their family can have varying barriers.

Sense has, to date, facilitated a number of sport and physical activity related sessions in local communities using knowledge and understanding of the needs and barriers for families and their children when taking part in sport and physical activity. However, a public inquiry conducted by Sense in 2016, ‘Making the Case for Play’(15), highlighted a number of key issues with access to play, family experiences, play provision, and barriers caused by policy on a local and national level.

A total of 21 recommendations were provided to tackle areas where changes were needed to improve access to play for children with multiple needs. Parents play a key role in helping disabled children to be physically active as they are the primary advocate to participate and provide financial and practical support to facilitate engagement.(9)

Therefore, Sense commissioned the ukactive Research Institute to undertake a research consultation with the aim of understanding the complex physical activity needs of families who have children with complex disabilities. Specifically, this included understanding the challenges, barriers, and motivations of parents and carers of children with disabilities to be physically active, as well as their opinion on delivery frequency and timing. This involved parents and carers who both did and did not access Sense services.

Methodology

To meet the aims of the research project and to provide an insight into the needs that families who have children with complex disabilities are facing, the ukactive Research Institute developed a mixed-methods research approach.

This approach included a survey to parents and carers of children with complex disabilities followed by focus groups with the same population to explore areas in greater detail.

This research started before the coronavirus pandemic began in early 2020 and as such the research aims and objectives did not focus and do not make specific reference to Covid-19, as is reflected in the data collected. However, the focus groups were undertaken throughout the pandemic, and while questioning still focused on the project’s original aims, some of the data captured refers to changes that have occurred as a result of the UK Covid-19 lockdowns. Where relevant the findings from this research have been linked to enforced changes to delivery or the approach taken by Sense during this period of the pandemic.

Online survey

An online survey was developed to capture information from parents and carers of children with complex disabilities. The survey was live between January and March 2020. This was undertaken across the combined networks of Sense and ukactive through general newsletters, specific groups and social media.

The questions looked to capture information on motivations, engagement opportunities, challenges and barriers, likelihood of attending specific activities, the importance of physical activity on key aspects of health, when activity participation works best and demographic information.

The responses were initially analysed to draw out the key findings and themes to inform the focus groups.

Focus groups

Key findings from the survey identified a need to explore the lived experiences of families of children with complex disabilities in more detail, especially centred on areas such as types of activity provisions, inclusivity and accessibility of these provisions and facilities for children with complex disabilities to be active, and perceived support needed from Sense associated to these areas.

Focus groups were used to explore these areas because of their suitability of gathering a deeper understanding of experiences, thoughts and opinions(16).

In particular, the key themes that emerged from the survey were explored with a range of individuals to provide a thorough, multi-levelled evaluation. Focus groups were undertaken in two stages virtually between 13 October 2020 and 15 March 2021.

This first stage included three in-depth hour-long focus groups and an hour-long interview with 12 parents and carers of children with complex disabilities. Participants included individuals who were and were not accessing direct support from Sense, and were conducted by the ukactive Research Institute.

After some initial data theming, it was agreed that a second stage should be undertaken to provide additional supplementary data around some of the prominent themes that emerged from the initial stages of focus groups specifically with families supported by Sense. The second stage included 12 15–20-minute interviews with 12 parents who were supported by Sense and were conducted by the ukactive Research Institute facilitated and supported by Sense Specialist Services for Children and Young People. All focus group and interview data were recorded, transcribed and analysed using thematic content analysis. This is a process of coding, theming and sub-theming which identifies recurrent patterns in the data and categorises patterns into prevalent groups or themes(17).

The themed data from the focus groups and survey data were combined and analysed collectively to identify overall key reoccurring themes and in order to develop the conclusions and recommendations shown in this report. Recommendations have been developed specifically for Sense’s services, however, they are also appropriate for use with the public, policymakers and wider stakeholders.

Results

Overall, 127 parents and carers of children with complex disabilities responded to the online survey. Their children were predominantly male (65.0%), with the 5 to 11-year-old group most represented (40.6%), followed by 12 to 16-year-olds (26.4%) and over 16-year-olds (25.5%). Overall, 30 different disabilities were reported with the most frequently disclosed being visual/hearing impairment (n=36), learning disability (n=29), ADHD/ ASD (n=16), and Cerebral palsy (n=15).

The same proportion of children had either one or two disabilities (28.9%), with just under one in four children having three disabilities, and just under one in five children having three or more disabilities. The most frequent comorbidity was visual/hearing impairment and learning disabilities. The West Midlands and West Sussex were the most represented regions of the UK. The opinions and experiences of 24 parents and carers were explored through the focus groups, who had children ranging from the ages of four up to 17 years old, with a variety of disability types and complexities.

Themes

Five themes were identified from the combined analysis from the survey and focus groups. These themes provide key areas that should be considered to develop and refine physical activity opportunities for children with complex disabilities.

Key themes highlight some of the factors that influence whether children with complex disabilities have access to and attend physical activity opportunities. These are:

- Motivations and barriers experienced by the parents and carers of children with complex disabilities

- Inclusivity by design (person-centred approach)

- Accessibility

- Communication

- Instruction

Each of these themes are explained in detail below, with aligning recommendations highlighted in the section after.

Motivations and barriers

As a part of the survey, parents and carers were asked about their motivations to engage their children in physical activity and the barriers and challenges that they face. Physical activity was rated important for a range of outcomes with physical health (4.71 out of 5) and happiness (4.69 out of 5) being the most important factors (Figure 1).

When asked to further describe motivations to engage children in physical activity, physical health was an important aspect which was made up of overall health, fitness, weight management and strength. Other areas of importance included enjoyment and stimulation, mental wellbeing, social interaction and inclusion.

Importance of physical activity and motivations to engage children in physical activity

On a scale of one to five, where one = not at all important and five = very important, how important do you think physical activity is for your child in relation to…

- Physical health – 4.71

- Happiness – 4.69

- Feelings of purpose – 4.48

- Mental health (anxiety/stress) – 4.41

- Social trust – 4.20

- Social connection and interaction – 4.58

Describe your motivations to engage your child in physical activity (n=119)

- Physical health – 39.8%

- Overall health – 52.4%

- Strength – 7.1%

- Weight management – 11.9%

- Fitness – 28.6%

- Enjoyment and stimulation – 15.2%

- Mental wellbeing – 14.7%

- Social interaction and inclusion – 12.8%

Although these motivations exist to engage children in physical activity opportunities, there are a number of barriers and challenges faced as a family when looking to engage their child in physical activity. The main barrier described by parents and carers was that there were limited activity options (n=35; Figure 2).

This included activities being too far away, the timing was not right for them, they were of poor quality and the access meant finding the right opportunities was difficult. Restricted access was specifically mentioned by 17 parents and carers and referred to inside and outside wheelchair access, as well as changing facilities.

The accessibility of facilities was also raised as a challenge in the focus groups, and determined whether or not parents and carers would or could take their children to certain activities and the distance they had to travel to take them to activities in accessible locations.

Another challenge to participation was that there can be an unwillingness to provide one-to-one support or adapt teaching (n=23). The latter, lack of willingness to adapt teaching, was of particular importance because it was also discussed at length in the focus groups and thus it has been explored in more depth in a section below (see Inclusivity by design).

Child motivation (n=14), cost (n=13) and lack of facility inclusion (n=11) were also described as challenges or barriers. Positively, time (n=5), safety concerns (n=4), and a lack of inclusivity by others (n=3) were only mentioned a handful of times suggesting the respondents were not experiencing these barriers regularly.

Respondents felt that there were more opportunities available for inclusive and disability-friendly activities for children in school settings than within the community.

Challenges and barriers to engaging children in physical activity

Limited activity options (e.g. distance/time/quality/access) – 35

Locations unable/unwilling to provide 1-1 support/adapt teaching – 23

Restricted access in facilities (inside and outside wheelchair) – 17

Child motivation – 14

Cost – 13

Lack of inclusivity by facilities (mindset & training) – 11

Lack of appropriate equipment in facilities (e.g. hoists in pools) – 9

Mental health of child (e.g. anxiety, panic attacks) – 7

Lack of family-inclusive activities – 6

Time – 5

Lack of knowledge of where to find information on activities – 4

Safety concerns – 4

Lack of inclusivity by others/discomfort – 3

Childcare for other children – 2

The motivations and barriers identified here build upon those previously identified within published literature. For motivations to engage children with complex disabilities in physical activity, previous research has suggested that the choice of activity should be given to the child and that inclusive pathways encourage continuous participation as children grow(9).

Parents and carers of children with complex disabilities reported and spoke frequently about the importance of physical activity opportunities adopting a person-centred approach or being inclusive in their design, including being catered, designed, developed and led with individual needs in mind. This was particularly concentrated on ensuring that assumptions were not made about the needs of their children, but rather adopting a person-centred approach which might require flexibility in how sessions were led or designed based on the needs of those attending, rather than developing a ‘one size fits all’ approach.

This also applied to having physical activities that were suitable for older children (14-17 years), which a majority of parents with older children agreed were limited in availability. Parents and carers with older children noted that the majority of physical activity sessions were aimed at younger age groups, but because of the lack of other suitable opportunities for older age groups, they took their children to these sessions even though they were not physically challenging enough.

As an alternative to having physical activities catered, and thus advertised towards different ages, these parents and carers suggested the activities be catered more towards need or ability level, and be categorised by intensity or complexity levels.

It was often mentioned that even in activities catered towards children with complex disabilities, parents and carers often found that those instructing the sessions held the expectation that all children with complex disabilities needed the same requirements or would follow a rigid session structure that often catered to only certain disabilities. They noted that this made it hard to find activities that were suitable for their children to attend, especially if their children required more one to one support, or if they needed to transport a lot of equipment.

Alternatively, activities were seen as suitable and enjoyable when the session focused more on understanding what worked for their children, the needs that they had and the things they were comfortable doing, and being courageous and creative enough to adapt the session structure to cater for those needs.

Parents specifically noted that this only happened when session instructors had no expectation, or put aside an expectation that a session had to run in a certain way, or that their children would participate in a set manner, and instead accepted that they would interact with the session in a way that worked for them. It also included having flexibility in the timings throughout the session to allow for time for practical things such as taking medication, having snacks or going to the bathroom.

Catering towards need, and being person-centred, went hand in hand with the concept of being open-minded, and instructors of the sessions not being afraid to use their imagination or take positive risks to try something new or different. Parents claimed they would seek out sessions run by individuals who had the imagination to adapt classes to suit their children’s needs and expand their own learning and skills to better cater for these needs, and that these were the kind of sessions that their children enjoyed the most and they continued to take them to.

Inclusivity by design (person-centred approach)

Three sub-themes fell under the theme of inclusivity by design, which can be seen in Figure 3.

- Inclusivity by design (person-centred approach)

- Cater by need

- Open-mindedness

- Flexibility in session delivery

Parents also felt that catering for individual needs was the way in which physical activity opportunities would become fully inclusive for their children, both disability-specific and mainstream activities, because it helped with the mentality of ‘expanding the normal’, instead of making disability an ‘other’ category which implies additional effort or imagination.

Lisa’s story

“I think as well, because [some of our children] can only take [the activities] in small chunks, if you’ve got a session that’s going on for an hour, a lot of our children, they can do five minutes, that’s what you’re gonna get from them. And so to have a really relaxed session, where you can dip in and out of it, is much more effective, I think. So we could go in for an hour, then he might walk around for half an hour to regulate. And then he might come back and do another five minutes, and then go off for ten and then think, oh, I’ll come back and you know, see what’s going on now. And that’s allowing him to be flexible and not feel if he has [to stay]. If he’s told he has to stay, we won’t be staying, because he’ll just kick off and we’ll be going home with him. I find that what works are the sessions that are very flexible, [where] it doesn’t matter because there’s not a time [limit for reaching an] end goal. The end goal is throughout the whole session… you [aren’t] learning a task, it’s like this task is just ongoing. And you can dip in and out of it as and when you choose.”

Lisa, parent

Sofia’s story

“If you have got, say, positive risk assessing occurring, I don’t see that there’s any barrier to doing [something different] other than how much you limit your imagination. I think we’re in danger of over-complicating it, particularly when we put people into boxes… and I think being disabled is not a good enough reason to be stuck in a box. I just think it means we’ve got to really think about it. Would it work like this? Would it work like that? Would this work? And then it’s asking the person that you’re working with … does that work for you?”

Sofia, parent

Accessibility

How accessible physical activities were for children with complex disabilities was influenced by four sub-themes: type of activity, availability of activities, frequency of activities and the format of activities (e.g. in-person or digital) (Figure 4).

- Accessibility of activities

- Type

- Availability

- Frequency

- Format

Type

As part of the survey, parents and carers were asked to rate (on a scale of one, not at all likely, to five, completely likely) the likelihood of attending a list of physical activities. This predetermined list was provided as the activities were either previously delivered by Sense as a one-off activity or families had expressed interest in the activities being provided.

Respondents also had the option of including their own activity preferences which were grouped by frequency during the analysis. Swimming (4.21 out of 5) and trampolining (4.02 out of 5) were the highest rated activities (Figure 5). Through the focus groups, parents also commented on these activities, plus horse riding and dance, as being popular for their children, because of the sensory aspect to them.

Further segmentation of the survey results indicated that parents were most interested in taking their children to types of physical activities that supported their social connection and interaction, mental health (e.g., reduced stress/anxiety) and that made their children happy, suggesting that these activity types were potentially the most popular because they were able to provide these three aspects.

Preference for activity type was not found to differ significantly between age or sex of the child, indicating it was likely based on individual need. Sailing (2.71 out of 5) and ice skating (2.76) were the least popular activities.

Figure 5. Physical activity popularity

- Additional activities

- Multi-sport 3.05

- Horse Riding 3.69

- Yoga 2.91

- Climbing 3.08

- Cycling 3.17

- Sailing 2.71

- Tennis 4.5 (n=6)

- Swimming 4.21

- Dance 5.0 (n=9)

- Ice Skating 2.76

- Walking/ Orienteering 5.0 (n=6)

- Trampolining 4.02

Listed activities (n=117)

Availability

When asked to provide their opinion on the availability of physical activity provisions for their children that parents and carers already knew about, used, or accessed, swimming and trampolining were again mentioned frequently, alongside school activities (Table 1). This suggests that preference for the activity mentioned above might be influenced by the availability of certain activities in terms of location and frequency.

This was a point raised in the focus groups by parents and carers, who often spoke about the limited activity availability in areas close to them, meaning that they had fewer activity type options to pick from. This aligns with the survey results which found that the most frequent opinion was that there were no inclusive activities or facilities near to the respondents, supporting the barriers and challenges findings already presented.

Table 1. Availability of physical activity provision for children with disabilities that parents and carers were aware of.

| Physical activity provision | Frequency mentioned | % of times mentioned |

| No inclusive activities or facilities nearby | 54 | 34.8% |

| Swimming | 19 | 12.3% |

| School activity/PE | 13 | 8.4% |

| Trampolining | 10 | 6.5% |

| Disability football | 7 | 4.5% |

| Dance (e.g. air dance) | 6 | 3.9% |

| Horse riding (RDA) | 6 | 3.9% |

| Hydrotherapy/pool | 6 | 3.9% |

| Personal trainer/physio/carer/one-to-one | 6 | 3.9% |

| Disability cycling | 5 | 3.2% |

| Park (e.g. special needs bikes) | 4 | 2.6% |

| Local gym | 3 | 1.9% |

| Multi-sport | 3 | 1.9% |

| Sense opportunities | 2 | 1.3% |

| Walk/run | 2 | 1.3% |

| Gymnastics | 2 | 1.3% |

| Soft play | 2 | 1.3% |

| Tennis | 2 | 1.3% |

| Rugby | 1 | 0.6% |

| Adventure sports | 1 | 0.6% |

| At home | 1 | 0.6% |

Frequency

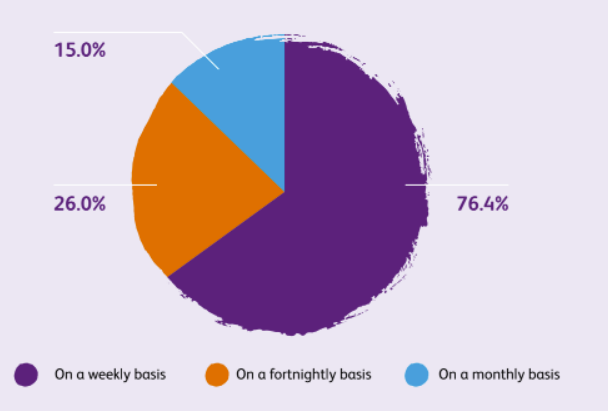

To understand in more depth how parents and carers wanted to engage in physical activity, questions were asked on how often and when activities should be delivered. Delivery on a weekly basis was the most popular (76.4%) frequency option (Figure 6).

The weekend was the most popular time of the week for delivery with 4 out of 5 respondents selecting Saturday and Sunday (Table 2). The weekdays had similar popularity to each other. From the specified list of school holiday periods, there was a general consensus that the autumn and summer half-term periods as well as Easter and summer holiday periods were popular with around three out of four parents and carers selecting these times of the year (Table 2).

Focus groups participants also stated a preference for activity availability in holidays because it mitigated barriers of lack of time (for travel) and tiredness that were more likely after school. Six respondents added in an open-ended response box that delivery all year round would be preferable.

Although all respondents did not have this as an option to select, the similar proportion of responses across the other options suggests that the majority would support year-round delivery, with the exception of festive holidays.

Figure 6. Delivery frequency popularity of physical activities.

- On a weekly basis – 76.04%

- On a fortnightly basis – 26.0%

- On a monthly basis – 15.0%

Table 2. Popularity of delivery by day of the week and across school holiday periods.

| Day of the week | n | % of sample | Time of the year | n | % of sample |

| Saturday | 105 | 82.7% | Half term – summer | 97 | 76.4% |

| Sunday | 102 | 80.3% | Easter holidays | 96 | 75.6% |

| Friday | 53 | 41.7% | Summer holidays | 95 | 74.8% |

| Wednesday | 50 | 39.4% | Half term – autumn | 94 | 74.0% |

| Thursday | 49 | 38.6% | Half term – winter | 91 | 71.7% |

| Tuesday | 48 | 37.8% | Festival holidays | 66 | 52.0% |

| Monday | 46 | 36.2% | All year round (in term time)* | 6 | 4.7% |

*This option was written as an ‘other’ response by six respondents and not a specified option to all respondents

Format

The parents and carers of children with complex disabilities were also influenced by the format in which activities were delivered, including if they were in person or digital, if they offered one-to-one or facilitator support and if the facility (location) was accessible.

Throughout the pandemic, a variety of online or digital sessions were hosted, which received overwhelmingly positive support from parents and carers who attended the focus groups. They felt these sessions were really supportive and well instructed because they allowed more time to focus on adaptation for different disability needs. By its very nature, the structure of these sessions was perceived as more flexible and allowed time to break down activities in a way that children could understand or helped parents and carers to think of ways they could adapt the exercises for their children.

Additionally, parents and carers also commented on the fact that digital sessions provided more opportunities for their children to engage because the sessions were easier and sometimes less stressful to attend than in-person ones, due to not having to travel long distances, coordinate care and manoeuvring of equipment, and knowing they were in an environment their children already felt comfortable and not anxious.

It was also noted by some parents that because the digital offers were not limited by location, it actually meant their children had a greater opportunity to interact with a wider group of children, which facilitated social interaction and making friends. While it was agreed that in-person sessions were valuable in other ways to online sessions, a majority of parents also felt that continuing the digital sessions alongside in-person sessions would be beneficial as part of an ongoing hybrid offer.

For in-person sessions, one-to-one support or additional facilitator and volunteer support to help with lifting/hoisting and or manoeuvring of equipment and belongings was also noted as extremely useful. A few parents noted that they were sometimes unable to take their children to certain activities, particularly the case for older children, because of a lack of volunteer support, or knowledge of volunteer support, because they were unable to lift their child by themselves.

This also extended to knowing that the format and layout of where the session would be hosted would allow them to easily access the building, and have room to store belongings safely. This fed into the session instructors having the flexibility to adapt the session structure, and not holding expectations about how their child would interact on the day.

Maria’s story

“I think having a more digestible expectation of the children on a day, it just makes it easier for everybody, because you’re not feeling like you’d have to achieve goals. [Sometimes] just getting there is an achievement, with everything else that you’ve got to take… lunch bags, spare clothes, strollers for them, or medical equipment [and] special feed, whatever it is, it’s thinking about those things. So a secure place where you can put your things and know that you can let your child go off and do whatever they need to do [and] you can be with them and can come back and get what you need. It’s just very practical, practical stuff, it needs to be a safe place where you’ve got plenty of space.”

Communication

Communication was a strong theme that emerged from the focus groups, and referred to three specific aspects: providing information on sessions, providing information on facility accessibility, and providing opportunities for support networks (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Communication sub-themes

- Communication

- Information on sessions

- Information on facility accessibility

- Opportunities for support networks

When asked if there was more support or information that Sense could provide around their physical activity opportunities, a majority stated that more information about what the sessions involved, notably what ability level or disability needs it could be adapted for (e.g. children who are deafblind, for wheelchair users) so they could make informed decisions about whether the session was suitable or could prepare ahead of time.

This applied to both in-person and digital sessions, however parents also noted that detail on digital sessions would be useful in different formats, such as video or verbal summaries so their children could also take on and prepare with the information.

Specific to in-person sessions, it was also noted that it was important to have information on the amount of support available and the accessibility of the facility the session was hosted in. Various parents commented that previously they had travelled long distances to reach a certain activity to find that either the facility was not accessible (e.g. did not have appropriate hoisting, changing, toilet, parking or wheelchair access) or that extra facilitator support was not available.

This additional facilitator or volunteer support was deemed extremely valuable by parents for completing practical tasks, such as lifting/hoisting older children and helping with manoeuvring equipment and belongings. The other way in which communication was considered important for parents and carers of children with complex disabilities was the opportunity to have more regular touchpoints with members of staff and other parents and carers who used Sense services.

Multiple parents were interested in the idea of a support network, facilitated by Sense, which would allow them to connect to, and receive information, support and advice from other parents who might have experienced similar situations or whose children might have similar needs. They also stated that this would be useful not just for understanding the activity opportunities for their children, but also as a social support and interaction opportunity for themselves as the parents or carers.

Instruction

The way sessions were delivered, and how engaged parents and carers felt their children were with them was also dependent on the individuals who instructed the sessions. Particularly, parents and carers noted that they would continue to take their children to sessions were instructors had the confidence to be flexible and try new things, had the skills and competence to adapt activities for different abilities and levels, and who took the time to build relationships with their children in order to understand their individual needs (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Instruction sub-themes

- Instruction

- Confidence

- Competence (skill)

- Builds relationships

“It’s good to [have people] you can trust… as a parent [knowing] that they actually have your child’s interests at hand and [to] have an understanding of what needs to happen.”

Laura, parent

Similar to the sub-theme of flexibility in session delivery, parents and carers wanted instructors that had the confidence to try new ideas with their children, and apply positive risk assessment to help identify the kind of activities or ways of operating that their children would enjoy and engage with the most.

This, they felt, required the instructors to have a level of competence and technical skill in adapting exercises for different ability levels or needs, including being able to communicate clearly about what the session involved or what the options for involvement were, including with children of different needs (e.g. use of sign as well as verbally). Where this was often most prominent, parents and carers reported that instructors took the time to build relationships with their children so they could get to know these specific needs and requirements.

Parents and carers also appreciated session instructors who took the time to obtain feedback, input and expertise from the parents and carers about what their children needed instead of making assumptions. Parents frequently expressed irritation at being told they could not stay for sessions with their children, or instructors not listening to their advice, because, due to their experience, they felt they understood their child’s needs better from the offset.

It was often noted that instructors who asked for feedback and input from parents and carers were the ones who had more experience or competence in working with children of different complex disabilities.

Clara’s story

“The riding school where I take my child is RDA approved, so that’s riders for disabled association, so the lady who’s been doing it has got extensive experience. She’s aware that there needs to be parent input, she’s very open to me saying, ‘Well, can you do it this way or this way’. That’s kind of what you want as someone who’s open to parent input because at the end of the day the parents actually know their child the best.”

Conclusions and recommendations

The five key themes presented above provide an insight into the challenges, barriers and motivations of parents and carers of disabled children in regards to being physically active, as well as their opinion on the important aspects of activity delivery and support. Through the combined survey, focus groups and interviews with parents and carers, the data findings demonstrate what can be done to better support and engage children with complex disabilities in physical activity.

The key themes highlight the need for ongoing and improved inclusivity and consideration of need when designing and delivering physical activity opportunities for children with complex disabilities, with a focus on adopting a person-centred approach to activity development, selection, availability, frequency and format so that activity sessions are centred around need and are more accessible to more children.

In addition to utilising a person-centred approach, having clear and detailed communication of physical activity sessions and strong and personable instructors to deliver and coordinate them were highlighted as key opportunities to increase the accessibility of the current (and new) physical activity opportunities.

Five recommendations

Based on these findings, five recommendations have been developed to provide tangible steps that sport and physical activity providers can take to encourage physical activity participation for children with complex disabilities. These recommendations are highlighted below.

Recommendation one

Cater physical activity opportunities by need, and categorise by intensity or ability instead of age so activities can be easily identified.

Recommendation two

Develop and design physical activity sessions utilising a co-creation, person-centred approach, ensuring access and engagement in suitable activities for a range of complex disabilities. Specifically:

- Sessions should be flexible in structure, delivery style and timing.

- Collect continuous feedback to modify activity frequency and type based on what is most popular.

- Ensure the availability of in-person sessions across different regions of the UK.

- Provide sessions in different formats (digital and online).

- Ensure there are appropriate numbers of delivery, support staff or volunteers to aid with practicalities of equipment manoeuvring and lifting of children (particularly older children) which can help provide better activity opportunities for older children with complex disabilities (e.g. 13 plus).

Recommendation three

Ensure communication of physical activity opportunities is clear and detailed to allow parents, carers and children to prepare. In particular, provide detail on:

- Content – what the session involves, including particular exercises, activities and structure.

- Ability level – what ability or intensity level is targeted.

- Adaptation – adaptation for different disability needs and which needs the session is most suitable for.

- Accessibility – of the facilities or location if the session is held in person, such as information on wheelchair access, close parking, hoists and accessible changing rooms.

Recommendation four

Provide and improve support networks for parents and carers to allow opportunities for individuals to socially connect and receive information, guidance and advice from others experiencing similar situations or whose children might have similar needs.

Recommendation five

Ensure physical activity sessions are being led by appropriate individuals who have the confidence, competence (skill) and interpersonal abilities to adapt sessions to cater towards need and build positive relationships with the children.

This research has indicated the importance of ensuring that physical activity offerings are inclusive for all children, no matter how complex their disability, to ensure they have equal opportunity to fulfil their potential, engage in social interaction and obtain physical and mental health benefits. It has been vital to obtain input and feedback from parents and carers around the barriers, motivations and feasibility of physical activity engagement for their children because they have a key role to play in encouraging physical activity participation for their children(9).

These report recommendations reflect clear steps, developed based on this feedback, that can be taken to make it easier for parents and carers to support their children to be active. Although activity levels are similar for children both with and without a disability or long-term limiting health condition(14) there are a range of motivators and barriers that may influence participation(7,8) and an estimated one million children in the UK are reported to have a disability(1,2) indicating the need to support this population to lead the same healthy lives as children without disabilities.

No one, no matter how complex their disabilities, should be isolated or left out from opportunities to maintain a healthy and active lifestyle.

This report and recommendations should be used as part of a clear implementation plan to ensure that children with complex disabilities and their families can get the best possible start through participation in physical activity.

References

- Department for Work and Pensions. Family Resources Survey: financial year 2019 to 2020. 2021

- Office for National Statistics. Estimates of the population for the UK, England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. 2021

- Department for Education. Special Educational Needs in England. 2016 14 (2016).

- Pinney, A. Understanding the needs of disabled children with complex needs or life-limiting conditions. (2017).

- Horn, E. & Kang, J. Supporting Young Children With Multiple Disabilities: What Do We Know and What Do We Still Need To Learn? 31, 241–248 (2011).

- Brown, H. E. et al. Family-based interventions to increase physical activity in children: A systematic review, meta-analysis and realist synthesis. Obes. Rev. 17, 345–360 (2016).

- Columna, L. et al. Physical activity participation among families of children with visual impairments and blindness. Disabil. Rehabil. 41, 357–365 (2019).

- Shields, N., Synnot, A. J. & Barr, M. Perceived barriers and facilitators to physical activity for children with disability: a systematic review. British journal of sports medicine vol. 46 989–997 (2012).

- Shields, N. & Synnot, A. Perceived barriers and facilitators to participation in physical activity for children with disability: A qualitative study. BMC Pediatr. 16, (2016).

- Strong, W. B. et al. Evidence-based physical activity for school-age youth. J. Pediatr. 146, 732–737 (2005).

- Tremblay, M. S. et al. Canadian 24-hour movement guidelines for children and youth: An integration of physical activity, sedentary behaviour, and sleep. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 41, S311–S327 (2016).

- Department of Health and Social Care. UK Chief Medical Officers’ Physical Activity Guidelines. (2019).

- WHO. WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. (2020).

- Sport England. Active Lives Children and Young People Survey: Academic Year 2019/20. (2021).

- Sense. Making play inclusive. (2021).

- Rabiee, F. Focus-group interview and data analysis. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 63, 655–660 (2004).

- Braun, V. & Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101 (2006).

This content was last reviewed in April 2022. We’ll review it again next year.